![gb_jones_bruce_labruce_1365091561_crop_550x569[1]](https://queercorebook.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/gb_jones_bruce_labruce_1365091561_crop_550x5691.jpg)

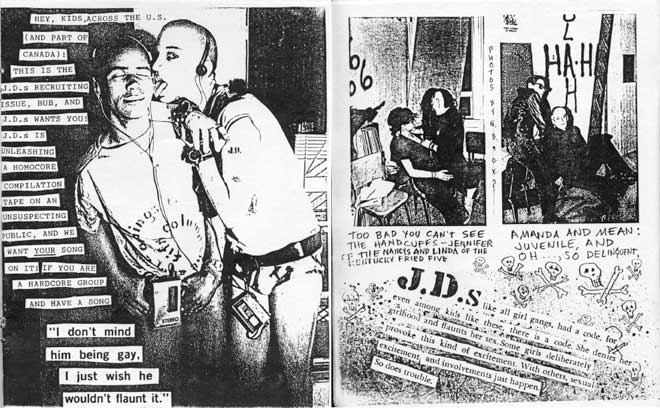

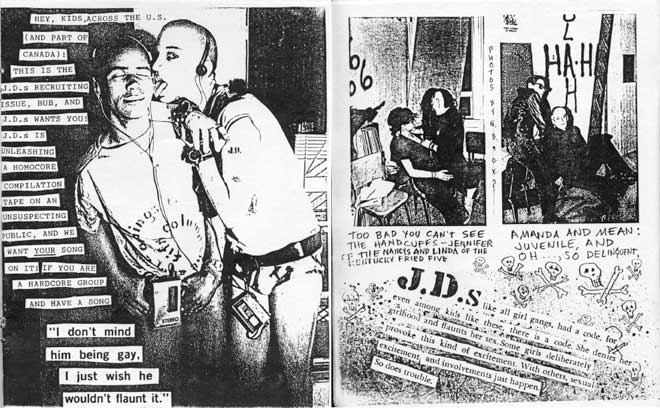

LaBruce and Jones in the pages of J.D.s

J.D.s #5 (1989)

Jones and LaBruce (with some help from others) published the first issue of J.D.s in 1985. Referring to themselves and their comrades as the “The New Lavender Panthers,” J.D.s served as a (sub)cultural platform from which to stage their attack on the sexism and homophobia in punk, while also speaking against the growing conservatism of the gay and lesbian mainstream–a conservatism that would eventually find expression in the politics of marriage and the military. These linked sentiments on the corrosive effects of mainstream punk and assimilationist gay/lesbian—two previously subversive parent cultures that had lost their way in the eyes of queercore’s instigators—were at the irritated core of J.D.s’ critical cultural intervention, and subsequent queercore art.

![Figure4.1[1]](https://queercorebook.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/figure204-11.jpg)

“bad seed” Vaginal Davis by Rick Castro

![slant5001[1]](https://queercorebook.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/slant50011.jpg)

Cover of Slant. 5 by Mimi Thi Nguyen

![Figure0.1Version1[1]](https://queercorebook.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/figure200-120version2011.jpg)

Album cover for God Is My Co-Pilot

![Figure1.3Version1[1]](https://queercorebook.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/figure201-320version2011.jpg)

Phranc & Gerardo Velazquez of Nervous Gender

![a1546949811_10[1]](https://queercorebook.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/a1546949811_101.jpg)

G.L.O.S.S. album cover

This abridged overview has been excerpted from Curran Nault’s Queercore: Queer Punk Media Subculture. To learn more about queercore, purchase the book HERE.

Questions? Comments? Write to me HERE.

![gb_jones_bruce_labruce_1365091561_crop_550x569[1]](https://queercorebook.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/gb_jones_bruce_labruce_1365091561_crop_550x5691.jpg)

![Figure4.1[1]](https://queercorebook.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/figure204-11.jpg)

![slant5001[1]](https://queercorebook.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/slant50011.jpg)

![Figure0.1Version1[1]](https://queercorebook.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/figure200-120version2011.jpg)

![Figure1.3Version1[1]](https://queercorebook.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/figure201-320version2011.jpg)

![a1546949811_10[1]](https://queercorebook.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/a1546949811_101.jpg)